When a Swedish birthday tradition triggered a strong emotional reaction in my wife, she demanded that our exchange student, Brigitte, leave immediately. But karma hit her hard the very next day. We needed Brigitte’s help, but would she save the people who had wronged her?

Nothing had been normal since Brigitte came to us last summer. Don’t get me wrong, she was a great kid, the kind of exchange student every host family dreams of getting.

But sometimes cultural differences sneak up on you when you least expect it.

The morning began quite normally. My wife Melissa was making her famous blueberry pancakes and our two kids, Tommy and Sarah, were fighting over the last of the orange juice.

Just another Tuesday in our family. Except it wasn’t just another Tuesday – it was Bridget’s 16th birthday.

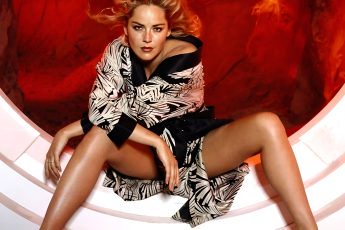

Footsteps were heard on the stairs, and everyone fidgeted, trying to look casual. Bridget appeared in the doorway, her long blonde hair still a mess from her nap. Her eyes widened as she looked round the kitchen, decorated with balloons and streamers enough for a small circus.

‘Oh my God!’ – she exclaimed, and her Swedish accent became even more distinct with excitement. ‘It’s… it’s too much!’

Melissa brightens, placing a stack of pancakes on the table. ‘Nothing is too much for our birthday girl. Come on, sit down. We’ll have presents after breakfast, and then you can call your family.’

I watched Bridget settle into the chair, looking both embarrassed and delighted by this attention. It was hard to believe she had only lived with us for two months. Sometimes I felt like she had always been a part of our family.

After breakfast and presents, we gathered around while Bridget chatted on FaceTim with her family in Sweden. As soon as her parents, brothers and sisters appeared on the screen, they started a song – some long, repetitive tune in Swedish that made everyone on both sides of the Atlantic laugh.

I didn’t understand a word, but Bridget’s face lit up like Times Square on New Year’s Eve.

‘Oh my God, stop it!’ – She giggled, her cheeks turning pink. ‘You’re so embarrassing!’

Her younger brother added some kind of dance move that made Bridget groan and cover her face. ‘Magnus, you’re the worst!’

After the song ended and we all wished her a happy birthday (in English and Swedish), we left her alone so she could socialise with her family.

I headed to the garage to check our emergency supplies. The weather channel broadcast a warning of a storm coming at us.

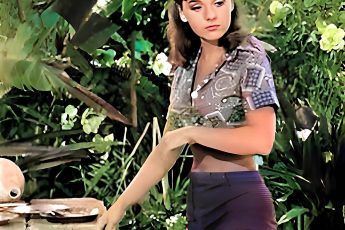

‘Hey, Mr Gary?’ Bridget appeared in the doorway as I was counting batteries. Her hair was swept back and she’d changed into one of the T-shirts she’d been given for her birthday. ‘Do you need any help?’

‘Thanks, babe.’ I gestured to the pile of torches I was checking out. ‘Actually, could you check them out? Just switch each one on and off.’ As she started checking, I asked: ‘Say, what was that song about? It sounded pretty funny.’

She grinned and started going through the torches.

‘Oh, that’s a silly tradition. When you turn 100 years old, the song talks about getting shot, hanged, drowned, that sort of thing. It’s supposed to be funny, you know?’

Before I could answer, Melissa burst through the door like a tornado in yoga pants. ‘What did you just say?’

The torch in Bridgette’s hand dropped to the floor. ‘A birthday song?’ Her smile faded. ‘It’s just…’

‘Just mocking death? Mocking the elderly?’ Melissa’s voice rose with each word, her face reddening. ‘How dare you bring such disrespect into our home!’

I tried to intervene by stepping between them. ‘Honey, it’s just a cultural thing…’

‘Don’t ‘honey’ me, Gary!’ Melissa’s eyes were blazing and I could see tears starting to accumulate in the corners of them. ‘My father was sixty when I was born. Do you know what it’s like to watch someone you love grow old and sick? And you sing songs about killing old people?’

Bridget’s face went from pink to ghostly white. ‘Mum, I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean to…’

‘Pack your things.’ Melissa’s voice was icy, each word dropping like a stone in the suddenly hushed garage.

‘I want you out of this house before the airports close for the storm.’

‘Melissa!’ I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. ‘You can’t be serious. She’s just a kid, and it’s her birthday!’

But Melissa had already stormed into the house, leaving Bridget in tears and us in shocked silence. Through the open door we could hear her stomping up the stairs, and then the slamming of her bedroom door.

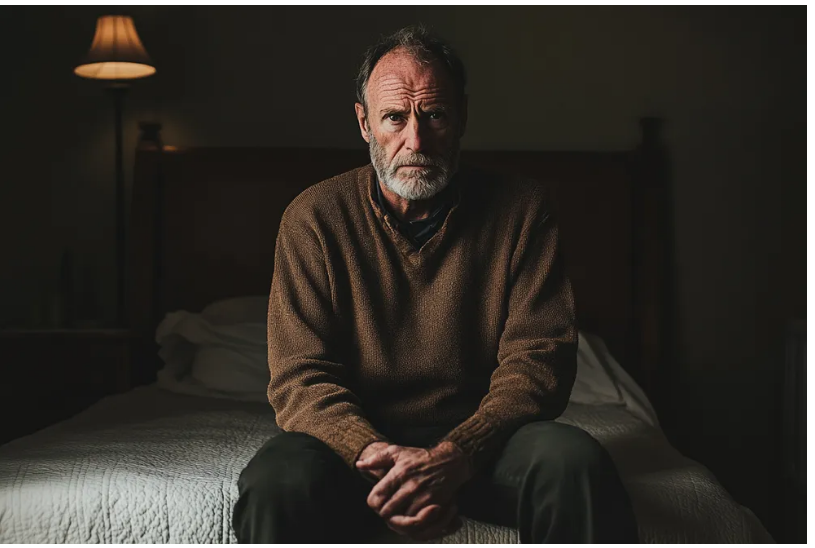

The next 24 hours were like walking through a minefield. Bridget stayed in her room, coming out only to use the loo. When I brought her dinner, I found her sitting on her bed surrounded by half-assembled suitcases.

‘I didn’t want to cause trouble,’ she whispered, not lifting her eyes from the shirt she was folding. ‘In Sweden we don’t… death isn’t such a scary thing. We joke about it sometimes.’

I crouched on the edge of her bed, trying not to disturb her careful packing.

‘I know, baby. Melissa…she’s still going through the loss of her father. He passed away four years ago, just short of his 97th birthday. She was there for him when it happened.’

Bridget’s hands froze on her shirt. ‘I didn’t know.’

‘She doesn’t talk about it often.’ I sighed, running a hand through my hair. ‘Look, just give her time. She’ll come round.’

But time wasn’t on our side. The next morning, the storm broke with renewed vigour.

It started with a few drops, and then the sky opened up as if someone upstairs had turned on a fire hose. The wind howled like a goods train, and the electricity flickered once, twice, and then completely gone. At that moment, the phone rang.

Melissa answered it, and I saw her face change. ‘Mum?’ Her voice was strained with worry. ‘Okay, calm down. We’re coming to get you.’

Helen, Melissa’s mother, lived alone in a small house a few blocks away. The storm was getting worse by the minute and we needed to bring her to her place.

I grabbed my mackintosh and car keys, but Melissa stopped me.

‘The road to Mum’s is probably already flooded. We need to walk, but it’s dangerous for us to go alone, and I don’t want to leave the kids here alone.’

As if on cue, Bridget appeared at the bottom of the stairs, fully dressed in her mackintosh. ‘I can help,’ she said quietly.

Melissa seemed about to object, but another roll of thunder made the decision for her. ‘Good. We can’t do this without you. Let’s go.’

The walk to Helen’s house reminded her of something out of an apocalypse film.

The rain slapped us in the face and the wind knocked us off our feet more than once. When we finally reached Helen’s house, she was sitting in an armchair and was calm.

‘Honestly,’ she said when she saw us and adjusted her glasses. ‘I’d be all right.’

But her hands trembled as she tried to stand up, and I noticed Bridget moving immediately to help her. The girl’s movements were confident and practised, as if she’d done it hundreds of times before.

‘In Sweden,’ Bridget explained as she helped Helen put on her mackintosh, ’I was a volunteer at an elderly care centre. Let me carry your bag, Mistress Helen.’

The walk back was even worse, but Bridget stayed one step away from Helen, shielding her from the wind and keeping up her pace with precision. I could see Melissa watching her, her expression unreadable in the stormy gloom.

By lunchtime, we were all gathered in the living room eating cold sandwiches by candlelight. The silence was deafening until Helen cleared her throat.

‘Melissa,’ she said, her voice soft but firm. ‘You’ve been awfully quiet.’

Melissa motioned her sandwich across her plate. ‘I’m fine, Mum.’

‘No, you’re not okay.’ Helen reached across the table and took her daughter’s hand. ‘You’re scared. Just like you were scared when your father was sick.’

The room grew even quieter, if that was even possible. Melissa’s eyes filled with tears.

‘Do you know what your father said about death?’ Helen continued, her voice warm from the memory. ‘He said it was like a birthday: everyone celebrates it sometime, so it’s best to laugh about it while you can.’

A sob escaped Melissa’s throat. ‘He was too young, Mum. Ninety-six is too young.’

‘Maybe,’ Helen agreed, squeezing her daughter’s hand. ‘But he lived each of those years to the fullest. And he wouldn’t want you to be afraid of a silly birthday song.’

Bridget, who had been quietly helping Tommy clear the plates from lunch, stopped short. Melissa looked up at her.

‘I’m so sorry, Bridget,’ Melissa whispered, her voice thick with emotion. ‘I was…I was awful to you.’

Bridget shook her head, her eyes glistening in the candlelight. ‘No, I’m really sorry. I should have explained it better.’

‘You…’ Melissa took a deep breath. ‘Will you stay? Please?’

And just like that, the storm inside our house began to quiet down, even though it was raging outside. As I watched Bridget and Melissa hugging each other and Helen glowering beside them, I realised one important thing: sometimes the worst storms bring out the best in people.

And sometimes a silly Swedish birthday song can teach you more about life and death than you ever thought possible.

Later that evening, as we all sat together by candlelight, Brigitta learnt a birthday song with us. And you know what? We all laughed. Even Melissa. Especially Melissa.