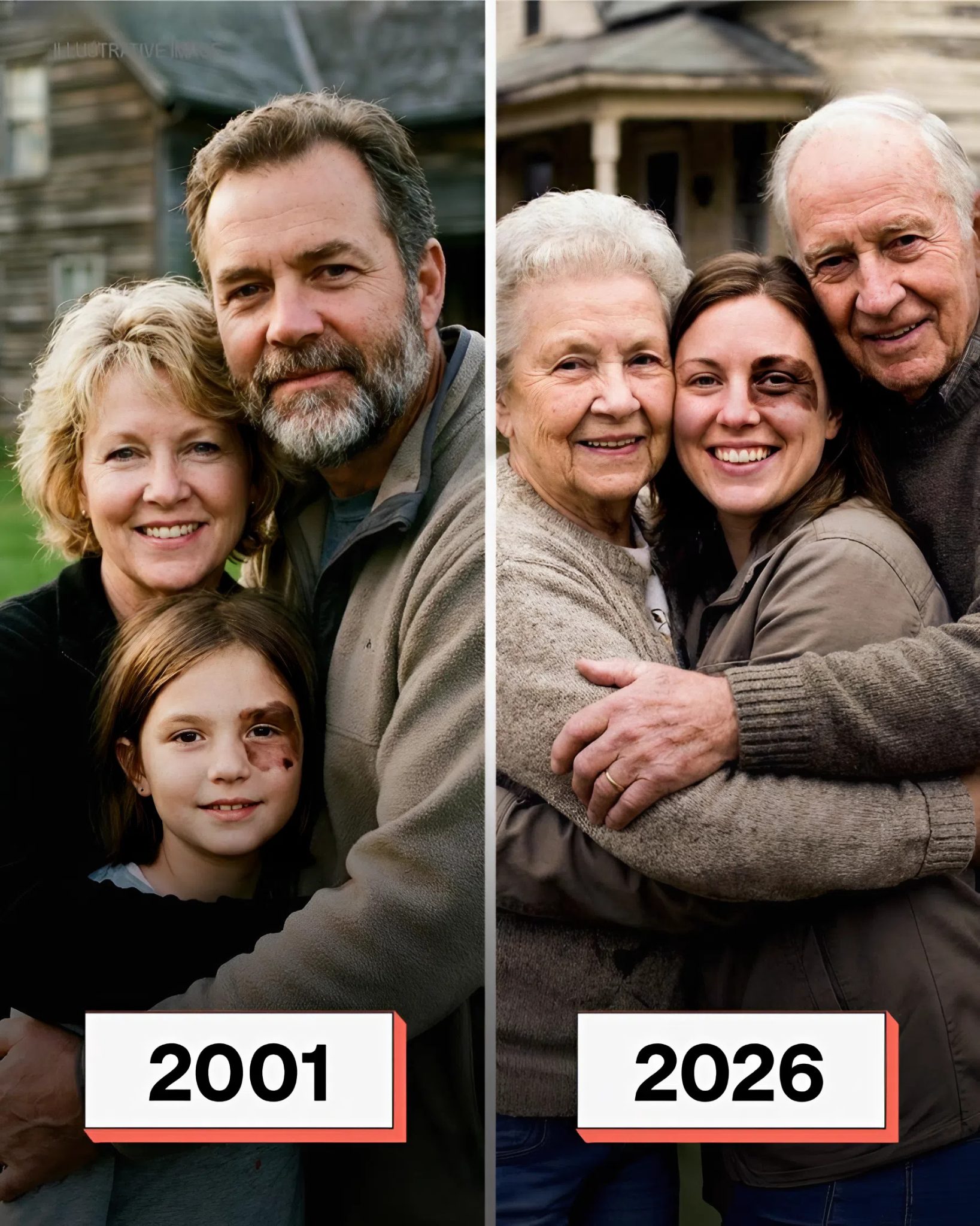

We adopted a little girl who had been rejected by others because of a birthmark covering half of her face. Twenty-five years later, we received a letter from her biological mother, and suddenly the past took on a different light.

I am 75 years old, Margaret. My husband, Thomas, has been my partner for over 50 years.

For a long time, it was just the two of us. We wanted children, very much. We tried for years. Tests, hormones, appointment after appointment. Then one day, the doctor clasped his hands together and said quietly, “Your chances are very low. I’m sorry.”

We thought we would get over it with time. There was no miracle, no plan B. Just a final sentence.

We mourned, then somehow settled in. By the time I turned 50, we were telling ourselves that we had accepted it.

Then our neighbor, Mrs. Collins, once mentioned a little girl in the children’s home who had been there since birth.

“Five years,” she said. “No one takes her. They call, ask for a photo, and then disappear.”

I asked her why.

“She has a large birthmark on her face,” she replied. “It covers almost one whole side. People see it and think it would be too difficult.”

That evening, I brought it up with Thomas. I expected him to say we were too late, too old, our lives too settled for this.

He listened, then said only, “You can’t get it out of your head.”

“No,” I admitted. “He’s been waiting his whole life.”

“We’re not young,” he added. “If we do this, we’ll be in our seventies by the time he grows up.”

“I know.”

“Money, energy, school, university,” he listed.

“I know.”

He listened for a long time, then said, “Would you like to meet him? Let’s just get to know him. No promises.”

Two days later, we entered the children’s home. A social worker accompanied us to a playroom.

“She knows visitors are coming,” he said. “We didn’t say any more. We don’t want to promise hope we can’t deliver.”

In the room, Lily sat at a low table, coloring carefully within the lines. Her clothes were a little big for her, as if they had been passed down too many times.

Her birthmark was dark and conspicuous, covering most of the left side of her face. Her eyes, however, were serious and observant. They were the eyes of a child who had learned early on to read adults before trusting them.

I knelt down beside her. “Hi, Lily. I’m Margaret.”

She glanced at the social worker, then back at me. “Hi,” she whispered.

Thomas sat down opposite her on a child’s chair. “I’m Thomas.”

Lily looked him up and down, then asked, “Are you old?”

Thomas smiled. “Older than you.”

“Will you die soon?” she asked with complete seriousness.

My stomach lurched. Thomas wasn’t fazed. “Not if I can help it,” he said. “I plan on being around for a long time.”

For a moment, a tiny smile slipped out of Lily, then she turned back to her coloring book.

She answered politely but gave little of herself. She kept looking at the door, as if measuring how long we would stay.

In the car on the way home, I said only this: “I want her.”

Thomas nodded. “Me too.”

The paperwork took months.

When it finally became official, Lily came out with a backpack and a worn-out stuffed rabbit. She held the rabbit by its ears, as if afraid it would disappear if she squeezed it too hard.

When we turned into the driveway, she asked, “Is this really my house now?”

“Yes,” I said.

“For how long?”

Thomas leaned back slightly in his seat. “Forever. We’re your parents.”

Lily looked at me, then at him. “Even if people stare?”

“People stare because they’re rude,” I replied. “Not because there’s anything wrong with you. We’re never ashamed of your face. Never.”

He nodded once, as if he had stored it away. I knew he would test us later to see if we were serious.

During the first week, he asked permission for everything. Can I sit here? Can I drink water? Can I go to the bathroom? Can I turn on the light? It was as if she wanted to fade into the background so we would be sure to keep her.

On the third day, I sat her down. “This is your home,” I said. “You don’t have to ask permission to exist.”

His eyes filled with tears. “What if I do something wrong?” he whispered. “Will you send me back?”

“No,” I said. “You might get punished. You might not get to watch TV. But we won’t send you back. You’re ours.”

He nodded, but he watched us for weeks. He waited for the moment when we would change our minds.

School was hard. The kids noticed. The kids said things.

One day he got in the car with red eyes, clutching his backpack like a shield. “A boy called me a monster face,” he grumbled. “And everyone laughed.”

I stepped aside. “Listen to me,” I said. “You’re not a monster. Anyone who says that has a problem, not you.”

He touched his face. “I wish it would go away.”

“I know,” I said. “I hate that it hurts. But I don’t want you to be anyone else.”

He didn’t answer, just held my hand all the way home, his fingers tight.

We never made a secret of the fact that we had adopted him. We said it from the beginning, we didn’t whisper it.

“You grew in another woman’s womb,” I told her once, “and in our hearts.”

When she turned 13, she asked, “Do you know anything about my other mother?”

“All we know is that she was very young,” I replied. “She left no name or letter. That’s all they told us.”

“So she just left you?”

“We don’t know why it happened,” I said. “We only know where we found you.”

After a short silence, she asked, “Do you think she ever thinks about me?”

“I think so,” I said. “You don’t forget a child you carried.”

Lily nodded and moved on, but I could see how tense her shoulders were, as if she had swallowed something sharp.

As she grew older, she learned to respond without shrinking back. “Birthmark,” she said. “No, it doesn’t hurt. Yes, I’m fine. Are you okay?” The older she got, the more confident she became.

At 16, she declared she wanted to be a doctor.

Thomas raised his eyebrows. “That’s a long way off.”

“I know,” she said.

“Why that?” I asked.

“Because I love science,” he replied, “and I want kids who feel different to see someone like them and know they’re not flawed.”

She studied hard, got into college, then medical school. It was difficult, sometimes brutal, but she didn’t give up.

By the time he graduated, we were slowing down. More medicine on the kitchen counter, more afternoon naps, more doctor’s appointments. Lily called every day, came every week, and scolded me about salt as if I were her patient. We thought we knew her whole story.

Then the letter arrived.

It was a simple white envelope. There was no stamp, no return address. Just “Margaret” in beautiful, neat handwriting. Someone had dropped it into our mailbox by hand.

There were three pages inside.

“Dear Margaret,” it began. “I am Emily, Lily’s biological mother.”

Emily wrote that she was 17 when she became pregnant. Her parents were strict, religious, and wanted to control everything. When Lily was born, they saw the birthmark and called it a punishment.

“They wouldn’t let me take her home,” she wrote. “They said no one would want a baby who looked like that.”

She also wrote that the hospital forced her to sign the adoption papers. She was a minor, had no money, no job, and nowhere to go.

“I signed,” she wrote. “But that didn’t stop me from loving her.”

She then confessed that when Lily was 3 years old, she went to the children’s home once and looked through a window. She didn’t have the courage to go in, her shame was too great. She went back later, and by then Lily had been adopted by an older couple. The staff said we seemed nice. Emily went home and cried for days.

The last page read: “I am sick now. Cancer. I don’t know how much time I have. I am not writing to take Lily back. I just want you to know that I had to. If you think it’s right, please tell her.”

I couldn’t move for a minute. It was as if the kitchen had tilted beneath me.

Thomas read it and then said, “We’ll tell her. It’s her story.”

We called Lily. She came over right after work, still in her hospital clothes, her hair tied back, her face tense, as if she were expecting bad news.

I pushed the letter toward her. “Whatever you feel, whatever you decide, we’re on your side,” I said.

She read it silently, her jaw clenched. She held it for a long time, then a tear fell onto the paper. When she reached the end, she sat motionless.

“It was seventeen,” she said finally.

“Yes,” I replied.

“And her parents did this.”

“Yes.”

“For so long, I thought she abandoned me because of my face,” Lily said. “But it’s not that simple.”

“No,” I said. “It rarely is.”

Then she looked up. “You and Thomas are my parents. That won’t change.”

The relief hit me so hard that I felt dizzy. “We’re not losing you?”

She snorted. “I’m not trading you in for a stranger, even if he is sick. You’re stuck with me.”

Thomas put his hand on her chest. “What love.”

Lily’s voice softened. “I think I want to meet him,” she said. “Not because he deserves it. Because I need to.”

We replied to Emily. A week later, we met in a small café.

Emily was thin and pale, wearing a scarf on her head. Her eyes were Lily’s eyes.

Lily stood up. “Emily?”

Emily nodded. “Lily.”

They sat down opposite each other, both trembling, but in different ways.

“You’re beautiful,” Emily said, her voice trembling.

Lily touched her cheek. “I look the same. That never changed.”

“I was wrong to let anyone tell you you were less than that,” Emily said. “I was afraid. My parents made decisions for me. I’m sorry.”

Lily touched her cheek. “I look the same. That never changed.”

“I was wrong to let anyone tell you that you were less than that,” Emily said. “I was afraid. My parents made decisions for me. I’m sorry.”

“Why didn’t you come back?” Lily asked. “Why didn’t you fight?”

Emily swallowed hard. “Because I didn’t know how,” she said. “Because I was scared, broke, and alone. That’s no excuse. I let you down.”

Lily looked at her hands. “I thought I’d be angry,” she said. “I am a little. But mostly I’m sad.”

“Me too,” Emily whispered.

They talked about Lily’s life, her home, and Emily’s illness. Lily asked medical questions, but she wasn’t trying to interrogate her, she just wanted to understand.

When it was time to leave, Emily turned to me. “Thank you,” she said. “Thank you for loving her.”

“She saved us too,” I replied. “We didn’t save her. We became a family.”

On the way home, Lily was quiet for a long time, looking out the window, as she used to do after difficult days at school. Then she suddenly broke down.

“I thought meeting her would fix something inside me,” she sobbed. “But it didn’t.”

I climbed into the back seat and hugged her.

“The truth doesn’t always heal,” I said. “Sometimes it just ends the guessing.”

She pressed her face into my shoulder. “You’re still my mom.”

“And you’re still my little girl,” I replied. “That’s for sure.”

Some time has passed since then. Lily and Emily talk sometimes. Sometimes they don’t talk for months. It’s complicated, and it doesn’t fit into a nice, neat story.

But one thing has changed forever.

Lily no longer says that she was “unwanted.”

Now she knows that she was wanted twice: once by a frightened 17-year-old girl who couldn’t stand up to her parents, and once by two people who heard about “the little girl that nobody wanted” and knew immediately that it was a lie.