Some photos send shivers down your spine, even if they aren’t meant to. An innocuous photo can seem disturbing when viewed through the lens of history or stripped of its context. Why does it seem so creepy? What is the story behind it?

Throughout time, cameras have captured moments that have sparked curiosity, anxiety, and countless questions. These haunting images weren’t created to be creepy, but their mysterious details or forgotten history make them unforgettable.

Sometimes finding out the truth behind them can relieve the tension, but other times it only adds to the mystery. Are you ready to uncover the stories behind these chilling echoes of the past?

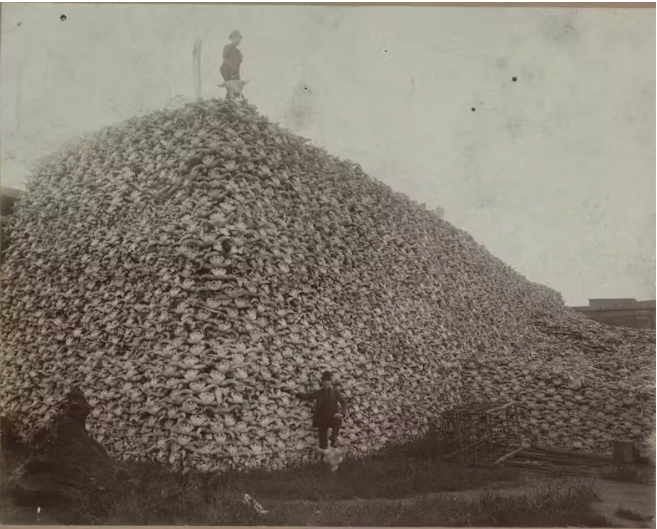

Mountain of Buffalo Skulls (1892).

This haunting photograph taken in 1892 outside the Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville, Michigan, captures a shocking moment in history. It shows a huge mountain of buffalo skulls collected for processing into bone glue, fertiliser and charcoal. What makes this image so disturbing is the story it tells – not just about the exploitation of natural resources, but about the massive losses associated with colonisation and industrialisation.

In the early 19th century, there were between 30 and 60 million bison in North America. By the time this photograph was taken, their numbers had dwindled to a staggering low of just 456 wild bison. Settler expansion westward, as well as market demand for bison hides and bones, led to the brutal extermination of the once thriving herds. Between 1850 and the late 1870s, most of the herds were destroyed, leaving behind both ecological and cultural devastation.

The towering pile of bones in this photograph is not just evidence of industrial greed; it also reflects the deep bond between indigenous peoples and bison, a bond forcibly severed by this massive destruction. The bones, stacked as a man-made mountain, blur the line between natural and man-made landscapes, a concept that photographer Edward Burtynsky later called ‘manufactured landscapes.’

Today, thanks to conservation efforts, some 31,000 wild bison roam North America. This photograph serves as a stark reminder of how close we came to losing them completely – a chilling look at a past shaped by choices that still echo today.

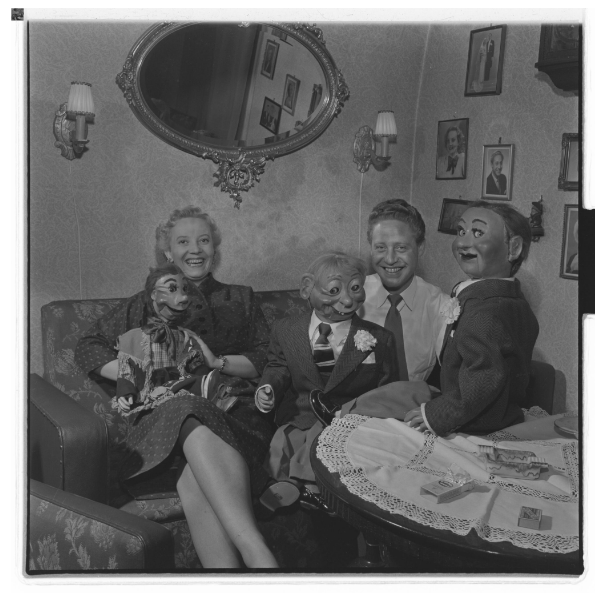

Inger Jacobsen and Bülow (1954)

This photograph from the mid-1950s may seem a little creepy at first glance, but it most likely captures an ordinary day in the life of Norwegian singer Inger Jacobsen and her husband, Danish ventriloquist Jacky Hein Bülow Jantzen, better known by his stage name Jacky Bülow.

Jacobsen was a favourite singer in Norway and even represented her country in the Eurovision Song Contest in 1962. At the same time, Bülow brought his unique charm and ventriloquist talent to audiences at a time when this art form was flourishing, especially on radio and nascent television.

Photography looks like a snapshot of a bygone era, a glimpse into a world that seems far removed from today. However, ventriloquism, while becoming less common, has not completely disappeared. The skill and creativity of ventriloquists continues to captivate audiences, and three performers – Terry Fator (2007), Paul Zerdin (2015), and Darci Lynn (2017) – have even won America’s Got Talent. It’s proof that the world may be changing, but some traditions continue to live on in unexpected ways.

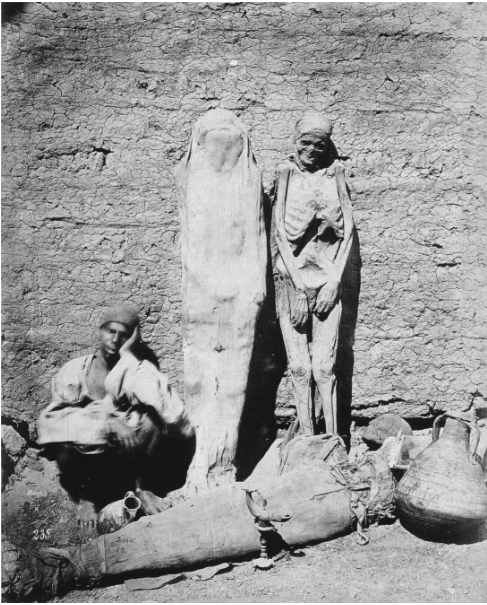

The Sleeping Mummy Trader (1875).

Mummies have always fascinated mankind, and ancient Egyptian mummies have captivated the imagination for over 2,000 years. But the way they have been treated throughout human history reveals a strange and sometimes disturbing story.

During the Middle Ages, Europeans used mummies for a variety of purposes: ground into powder to create supposed medicines, turned into torches because they burned so well, and even used them to treat ailments such as coughs or broken bones. The belief that mummies were embalmed with healing bitumen fuelled this trend, although this was not actually the case. By the 19th century, the medical use of mummies had waned, but interest in them remained.

Grave robbers fuelled the demand for mummies, and merchants shipped them from Egypt to Europe and America, where they became prized possessions of the wealthy. They were displayed as status symbols or used for research. One of the strangest trends of the 1800s was the ‘unwrapping party,’ where mummies were ceremoniously unwrapped in front of curious onlookers, blurring the lines between science and entertainment.

This image of a merchant resting amongst a multitude of mummies highlights how these ancient artefacts became a commodity that was used for a variety of purposes, from medical experiments to drawing room spectacles. It’s a reminder of how cultural treasures were once treated – and why their preservation is so important today.

Iron Lungs (1953)

Before the advent of vaccines, polio was one of the world’s worst diseases, paralysing or killing thousands of people every year. In the US, the worst was the 1952 outbreak, when nearly 58,000 cases were reported – leaving more than 21,000 people disabled and killing 3,145 people, mostly children. Polio does not damage the lungs directly, but affects motor neurons in the spinal cord, disrupting the connection between the brain and the muscles needed for breathing.

For the sickest patients, survival often meant confinement in an ‘iron lung’ – a mechanical respirator that kept them alive by forcing air into their paralysed lungs. Hospitals had rows of these towering cylindrical machines filled with children fighting for their lives. One image of these ‘mechanical lungs’ is enough to convey the devastating impact of polio, a chilling reminder of the fear and uncertainty that gripped families before the vaccine became available in 1955.

Even for those who emerged from the iron lung, life was never the same again, often remaining disabled. But the photograph above – the endlessly stretching rows of iron lungs – testifies to both the human cost of the epidemic and the resilience of those who fought to overcome it.

A young mother and her dead child (1901)

The ghostly image of Otilia Januszewska holding her recently deceased son Alexander in her arms not only captures a profound moment of grief, but also speaks to the Victorian tradition of posthumous photography. This practice, which became widespread in the mid-nineteenth century, served as a way to honour the deceased and preserve a final, tangible connection with loved ones, especially when the reality of death seemed too overwhelming.

The idea of reflecting on death is rooted in the concept of memento mori, which means ‘remember that you must die,’ and has deep historical roots. In the Middle Ages, reminders of death often appeared in paintings, and earlier cultures created trinkets depicting skeletons – a sombre but necessary acknowledgement of the fragility of life.

With the advent of photography in the nineteenth century, it became the perfect medium to make these reflections personal and intimate. Families who could now take photographs immortalised their deceased loved ones in an attempt to hold them so that their faces were always at hand. This allowed the living to grieve, but also created a strong bond, a sense of connection after death.

Interestingly, today, when a loved one passes away, we tend to focus on celebrating their life, often avoiding the harsh reality of their death – almost as if mentioning it directly was forbidden. In contrast, the Victorians embraced death enthusiastically, incorporating it into rituals that recognised its inevitable presence.

Posthumous photography, which reached its peak in the 1860s and 70s, was a key part of this process. It began in the 1840s with the invention of photography, and although not all Victorians were comfortable with photographing the dead, the practice became widespread, especially in Britain, the USA and Europe.

A 9-year-old female factory worker in Maine (1911)

In 1911, life for many working class families in America was reduced to hard work, long hours and making ends meet.

For Nan de Gallant, a 9-year-old girl from Perry, Maine, summer meant only one thing: working at the Seacoast Canning Co. factory in Eastport, Maine. She wasn’t running around in the fields or playing with her friends – she was helping her family transport sardines, working long hours alongside her mother and two sisters.

Child labour was unfortunately common in early 20th century America, especially in industries such as canning, textiles and agriculture. Families were helped by every extra pair of hands. But for children like Nan, it meant sacrificing childhood. By age 9, she was already working, which unfortunately was not uncommon for children her age at this time. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics, in 1910, 18% of children between the ages of 10 and 15 were working.

Maine had a law prohibiting children under 12 from working in manufacturing, but it did not apply to canneries that produced perishable foods. That law changed in 1911, but it’s hard to say how much of an impact it had on the lives of children like Nan.

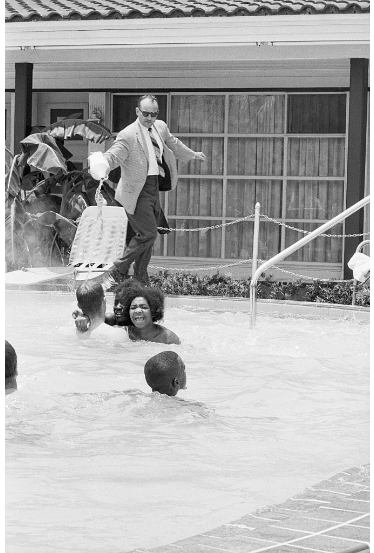

James Brock pours acid into a swimming pool (1964)

In 1964, a chilling photograph captured motel manager James Brock pouring muriatic acid into the Monson Motor Lodge pool to prevent black swimmers from using it.

The act followed an attempt by a group of black activists to integrate segregated space in St Augustine, Florida. Instead of allowing equality, Brock decided to destroy the pool.

The photograph, taken by Charles Moore, symbolises the deep-rooted racism of the time and the courage of those who fought for civil rights. Today, it serves as a reminder of how far we have come and how far we still have to go in the fight for equality. It teaches us resilience, the power of resistance, and the need to confront the uncomfortable truths of our history.

Coal miners return from the depths (C.1900)

In the early 1920s, Belgian coal miners endured hard days underground, working in dangerous conditions to provide fuel for the growing industrial revolution. After hours of gruelling labour in the dark, they would cramp into a crowded lift and finally emerge into the light. The creaking of the lift and the quiet hum of their voices show how much they depended on each other.

Their faces, covered in coal dust, told a story of hard work and sacrifice. Every wrinkle and feature testified to how hard their work was for them, but at the same time reflected their pride in their labour. These men kept the industry moving, even if it was at the cost of their health and safety.

When they finally stepped out into the daylight, it was a vivid reminder of the contrast between the darkness of the mines and the bright light overhead. But even more than that, it was a reminder of their strength and resilience. They had each other, and together they kept going forward. Their bond, forged through their shared struggles, was the heart of their community – they faced hardship side by side no matter what.

Fingerprints of Alvin Karpis (1936)

Alvin ‘Creepy’ Karpis, a notorious criminal of the 1930s, was a member of Barker’s gang and engaged in high-profile kidnappings. After leaving fingerprints on two major crimes in 1933, he attempted to erase his identity.

In 1934, he and fellow gang member Fred Barker had cosmetic surgery from Chicago doctor Joseph ‘Doc’ Moran. Moran altered their noses, chins and jaws and even froze their fingers with cocaine to scrape off fingerprints.

Despite these efforts, Karpis was caught in New Orleans in 1936, sentenced to life in prison and spent more than 30 years behind bars, including a stay on Alcatraz. He was paroled in 1969.

Halloween costumes in 1930

During the Great Depression, as violence and vandalism increased, communities began to create traditions such as handing out candy, having costume parties and organising haunted houses to discourage disorderly conduct. This era also saw more costume options for children, which added fun to the celebrations.

Two men making a death mask (c. 1908)

Death masks have long been used to preserve the appearance of the deceased. The ancient Egyptians, for example, created detailed masks to help the dead navigate the afterlife. Similarly, the ancient Greeks and Romans created statues and busts of their ancestors, laying the groundwork for the postmortem masks that came later.

What distinguished posthumous masks from other images was their realism. Unlike idealised sculptures, these masks were designed to convey the true features of the person, creating an indelible tribute. Famous figures such as Napoleon, Lincoln and Washington had posthumous masks made, which were then used for statues and busts that immortalised them long after their deaths.

Is there an image you missed or one you saw that you liked? What do you think of all these creepy paintings? Which one left the strongest impression? Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments