From “Ugly” to Unstoppable: How She Became the Sexiest Woman Alive

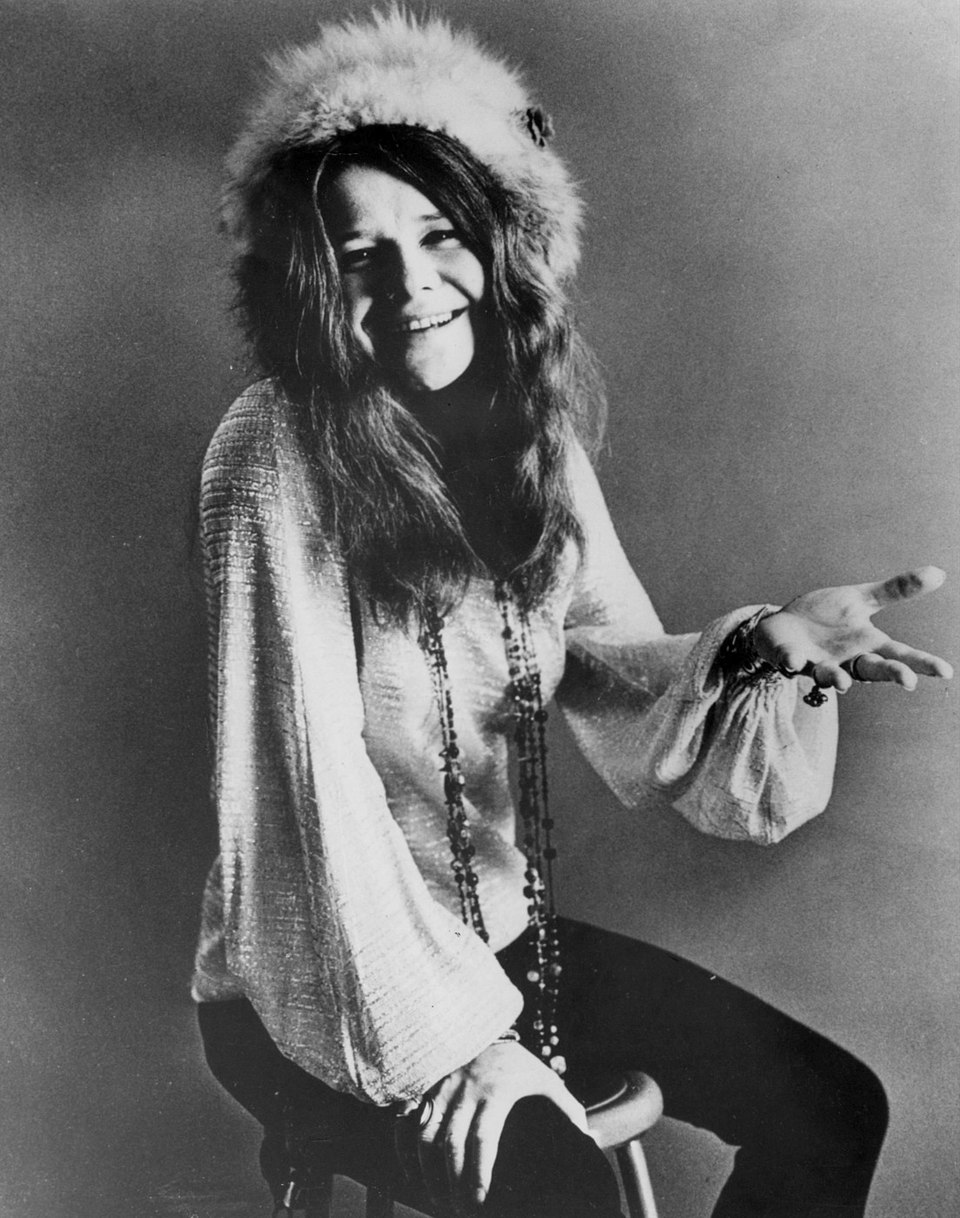

To me, she was slim and strong, with thick hair and striking eyes that carried a natural, almost Native beauty. She didn’t need makeup. And when she sang, it sounded like something lifted straight out of heaven.

On January 19, 1943, a baby girl was born in Port Arthur, Texas. Her parents were ordinary, hardworking people living a quiet life: her mother, Dorothy, worked at a local college, and her father, Seth, was an engineer at Texaco.

They were deeply religious and wanted a calm, God-centered home. But it didn’t take long to see their daughter was different. She demanded more attention, carried an unmistakable intensity, and seemed determined to be her own person from the start.

Growing up in Port Arthur meant growing up in a rigidly segregated town at a time when integration was fiercely contested—this was the era of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. She and the friends she gravitated toward stood out as the town’s bookish, intellectual liberals, hungry to understand the world beyond their streets and curious about the African-American experience. They devoured beatnik writing, fell in love with jazz, and listened closely to folk blues.

She became Port Arthur’s first female beatnik, frizzing her hair by drying it in the oven, refusing to wear a bra, and developing a laugh so distinctive a friend later remembered her asking, “Was it irritation enough?”

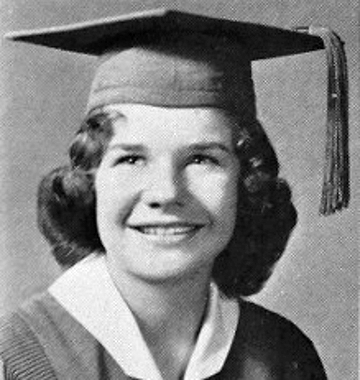

In high school, she discovered she loved singing—especially blues and folk—but those years were painful. She was bullied relentlessly and pushed to the margins socially.

As a teenager, she also struggled with weight and severe acne that left visible scarring. The scars were significant enough that she later pursued procedures to soften their impact. One former classmate, recalled in Alice Echols’ biography, put it bluntly: “She’d been cute, and all of a sudden she was ugly.” Her younger sister Laura described her skin as “a never-ending series of painful bright red pimples.”

She enrolled at a local college and later transferred to the University of Texas at Austin. On campus, she lived by her own rules—going barefoot when she felt like it, wearing Levi’s to class for comfort, and carrying her autoharp everywhere so she could sing whenever the urge hit.

“She ran with a tight group who hung out with books and ideas,” Laura remembered in a documentary.

In 1962, while at UT Austin, she nearly “won” a campus contest for the “ugliest man on campus.” Whether she entered as a joke or nominated herself is unclear, but people who were there agreed it left her humiliated.

“She felt like an outsider. She couldn’t identify with the same goals and desires that a lot of her classmates had,” her sister said.

That fixation on her appearance followed her for years and, at times, threatened to eclipse what mattered most: her talent. People questioned whether someone who looked like her belonged on a stage, and she felt that judgment sharply.

But there was one thing no one could deny.

Her voice.

Her climb began in January 1963, when she dropped out of college and hitchhiked to San Francisco, chasing a life in music. She sang in coffeehouses, survived on whatever support she could find, and left audiences stunned by how raw and powerful she sounded. Still, in the early 1960s, many record labels were searching for young women who fit a polished, conventional image—an image she never tried to be.

Her gift fit naturally into the folk world, which was still largely underground and less controlled by commercial expectations.

Back in Austin, she had already gained a reputation for heavy drinking. In San Francisco, it escalated, and she became entangled in the city’s drug culture. Speed was legal and easy to obtain at the time; when it became harder to find, she turned to heroin. She later told a reporter, in an extremely blunt way, that she wanted to use drugs constantly.

As her career intensified, she increasingly leaned on heroin to numb pressure and fear—especially the strain of being a solo artist under a spotlight that felt unforgiving. Throughout her life, she also experimented with other mind-altering substances and drank heavily, often favoring Southern Comfort.

After two years in San Francisco, she was in terrible shape. By 1965, she returned to Texas weighing only six stone and spent a year trying to rebuild her life. Old classmates suddenly saw her dressed neatly, wearing makeup, hair pulled back into a bun. She entered therapy, re-enrolled in college, and even considered becoming a secretary.

Then the call came: come back to San Francisco and sing with a new band—Big Brother and the Holding Company. And just like that, the old plan vanished.

While she had been away, San Francisco had become the epicenter of a cultural revolution, and she was about to become one of the defining voices of the counterculture.

In June 1966, the band played the Monterey Pop Festival, originally slotted for a low-profile afternoon set. The moment she sang, the audience erupted, and the band was moved to a prime evening slot the next day. Bob Dylan’s manager noticed them and signed them to Columbia Records for $250,000.

Monterey became their breakthrough—both for the band and for their electrifying lead singer. Almost overnight, the woman once mocked for her looks was treated as magnetic and glamorous. She spoke openly about her love life, kept the press watching, and even told Rolling Stone about a one-night encounter with football star Joe Namath. Rumors also swirled about a fling with talk show host Dick Cavett, who interviewed her more than once.

“I’m not a warthog that nobody wants to climb in bed with. Everyone want to climb in bed with me,” she said.

She became the first female rock star to reach true celebrity and icon status, appearing on major magazine covers like Newsweek and Rolling Stone.

And by now, the name is unmistakable.

It was Janis Joplin.

American singer-songwriter Janis Joplin posing for a portrait in San Francisco, United States circa 1967-1968. (Photo by Ray Andersen/Fantality Corporation/Getty Images)

Long before filters, viral makeovers, and cosmetic trends, Janis Joplin became a real sex symbol for a reason that had nothing to do with perfection: her voice projected beauty, force, and emotional truth. After recording two albums with Big Brother, she moved forward on her own—first with the Kozmic Blues Band and later with the Full Tilt Boogie Band.

She ultimately scored five hits on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, including her posthumous number-one cover of Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee,” which reached the top spot in March 1971.

Her most unforgettable songs include her fierce interpretations of “Piece of My Heart,” “Cry Baby,” “Down on Me,” “Ball and Chain,” and “Summertime,” along with “Mercedes Benz,” her final recording.

Her musical heroes included Odetta, Billie Holiday, and Otis Redding, but the artist who may have shaped her most deeply was blues legend Bessie Smith. Janis was outraged that Smith had been buried in an unmarked grave in Philadelphia. In August 1970, she partnered with Juanita Green—who had worked for Smith as a child—to pay for a proper headstone, finally giving Smith the tribute she deserved.

Looking back, it’s also clear Janis carried a strong need to please her parents. Amy Berg’s feature-length documentary Little Girl Blue draws on Janis’s letters to show how often she tried to justify her life choices to her family back in Port Arthur.

“Weak as it is, I apologize for being just so plain bad in the family,” she wrote after leaving for San Francisco.

Even as she rebelled, her parents largely supported her, though they worried about her drug use. In the documentary, Laura says their parents even questioned whether their shortcomings had “caused a calamity.” Yet at least once, they invited friends to their home to watch their daughter perform on The Ed Sullivan Show.

Laura later explained that their parents were proud, but also products of their generation—unable to fully understand the hippie movement. Still, they chose to stay close. They had learned to “agree to disagree,” believing the relationship mattered more than forcing compliance. They worried, as parents do, but they kept the lines of communication open in hopes they could still influence and protect her.

Tragically, Janis Joplin died far too young. She was 27 when she was found dead at the Landmark Hotel in Los Angeles in October 1970. She was discovered by her road manager and close friend, John Byrne Cooke.

Reports indicate she had spent time in the studio that day and seemed in good spirits, though a boyfriend and girlfriend she expected to meet never arrived. At the time, she was involved with two partners: her fiancé, Berkeley student Seth Morgan, and Peggy Caserta, with whom she had an on-and-off relationship.

Later, she returned to her hotel and died from a heroin overdose. It was later reported that the heroin she used that night was unusually pure, and the same batch also killed eight other people in Los Angeles that weekend.

Janis Joplin was cremated at Pierce Brothers Westwood Village Memorial Park and Mortuary in Los Angeles, and her ashes were scattered over the Pacific Ocean from a plane.

Through it all, Janis remained grounded in the way that mattered: she loved her music, and she loved the people who listened. She wasn’t just performing for a movement—she was part of it, its voice and its nerve center, both audience and icon at once.

Thank you for everything, Janis.