My classmates laughed at me because I am the son of a refuse collector. But at the graduation ceremony, I said one sentence, and the whole school fell silent and began to cry.

My name is Liam, and the smells of diesel fuel, bleach, and old food rotting in plastic bags have always been a part of my life.

My mum didn’t dream of collecting rubbish from 4 a.m. She wanted to be a nurse. She studied at medical college, got married, and lived in a small flat with her husband, who worked as a builder.

But one day, his insurance failed.

My life has always smelled of diesel, bleach, and old food rotting in plastic bags.

He fell and died before the ambulance even arrived. After that, we constantly struggled with hospital bills, funeral expenses, and everything she owed for her studies.

She immediately went from being a ‘future nurse’ to a ‘widow without a degree and with a child.’ No one wanted to hire her.

The city sanitation service didn’t care about diplomas or gaps in resumes. They were only interested in one thing: whether you showed up before dawn and kept coming back.

She instantly went from being a ‘future nurse’ to a ‘widow without a degree and with a child.’

So she put on a reflective vest, started working in the back of a truck, and became a ‘garbage collector.’ Meanwhile, I produced ‘the garbage collector’s son.’ That nickname stuck with me. In primary school, the kids wrinkled their noses when I sat next to them.

‘You smell like a garbage truck,’ they would say.

‘Be careful, he’ll bite.’

By the time I reached secondary school, it had become commonplace.

The other children would wrinkle their noses when I sat down next to them.

If I walked past, people would slowly cover their noses. If we worked in groups, I was always chosen last.

I memorised the layout of all the school corridors because I was always looking for places where I could eat alone.

My favourite spot was the corner behind the vending machines near the old theatre. Quiet. Dusty. Safe.

I was always looking for places where I could eat alone.

But at home, I was a different person.

‘How was your day, my love?’ my mother would ask, taking off her rubber gloves, her fingers red and swollen.

I kicked off my shoes and leaned on the table. ‘Everything was fine. We did a project. I sat with my friends. The teacher says I’m doing well.’

She smiled happily. ‘Of course. You’re the smartest boy in the world.’

At home, I was a different person.

I couldn’t tell her that sometimes I didn’t say more than ten words a day.

That I ate lunch alone. That when her truck turned onto our street while the children were there, I pretended not to notice her greeting.

She was already burdened with grief over my father’s death, debts, and double shifts.

I didn’t want to add ‘my child is unhappy’ to her problems.

I swore to myself: if she was going to work hard for me, I had to make her efforts worthwhile.

I swore to myself: ‘If she’s going to break herself for me, I’ll make it worthwhile.’

Education became my plan of salvation.

We didn’t have the money for tutors or preparatory courses. I had a library card, a worn-out laptop that my mum bought with money from selling recyclables, and a lot of perseverance.

I stayed in the library until closing time, studying algebra, physics, or whatever else I could find.

We didn’t have money for tutors or prep courses.

In the evenings, my mother would pour bags of cans onto the kitchen floor to sort them.

I would sit at the table doing my homework while she worked on the floor.

Every time, she would nod at my notebook.

‘Do you understand all this?’ she would ask.

‘Do you understand all this?’

‘Mostly,’ I would reply.

‘You’ll go further than I did,’ she would repeat, as if it were a fact.

High school started, and the jokes became quieter but sharper.

People no longer shouted ‘garbage man.’

High school started, and the jokes became quieter but sharper.

They started doing things like:

Moving my chair back an inch when I sat down.

Making fake retching noises under their breath.

Passing photos of the garbage man around and laughing, glancing at me.

If there were group chats with photos of my mum, I never saw them.

I could have told a counsellor or teacher.

Moving chairs even an inch when I sat down.

But then they would call my parents.

And my mum would find out.

So I put up with it and focused on my grades.

And then Mr Anderson came into my life. He was my maths teacher in Year 11. He was in his late 30s, his hair was messy, his tie was always askew, and he always had coffee with him.

And then Mr Anderson came into my life. He was my maths teacher in Year 11. He was in his late 30s, had messy hair, always wore a tie, and always had coffee with him.

One day, he walked past my desk and stopped. I was doing extra problems that I had printed out from the college website.

One day, he walked past my desk and stopped.

‘That’s not from the book.’

I jerked my hand away as if I had been caught cheating.

‘Um, yes. I just… like this.’

He pulled up a chair and sat down next to me as if we were equals.

‘Do you like this subject?’

‘It makes sense. Numbers don’t care what your mother does for a living.’

He looked at me for a few seconds, then said, ‘Have you ever thought about becoming an engineer? Or studying computer science?’

I laughed. ‘Those schools are for rich kids. We can’t even afford the application fees.’

‘Have you ever thought about becoming an engineer? Or studying computer science?’

‘There are fee waivers,’ he replied calmly. ‘There is financial aid. Smart poor kids exist. You’re one of them.’

I shrugged, embarrassed.

Since then, he has been my unofficial coach.

He gave me old competition problems ‘just in case.’ I could eat lunch in his classroom, claiming that he needed help grading papers.

He talked about algorithms and data structures as if they were gossip.

Since then, he has become my unofficial coach.

He also showed me websites for schools I had only heard about on television.

‘Places like these would fight for you,’ he said, pointing to one of them.

‘Not if they see my address,’ I muttered.

He sighed. ‘Liam, your postcode isn’t a prison.’

‘Liam, your postcode isn’t a prison.’

By my senior year, my GPA was the highest in the class. People started calling me ‘the smart guy.’ Some said it with respect, while others considered it a disability.

‘Of course he got an A. He doesn’t have it easy.’

‘The teachers took pity on him. That’s why.’

Meanwhile, my mum worked double shifts to pay the latest hospital bills.

One day after class, Mr Anderson asked me to stay behind.

He placed a brochure on my desk. It was large, with a fancy logo. I recognised it immediately.

It was one of the best engineering schools in the country.

He placed the brochure on my desk.

‘I want you to apply here,’ he said.

I stared at it as if it might catch fire.

‘Yeah, right. That’s funny.’

‘I’m serious. They have full scholarships for students like you. I checked.’

‘I can’t just leave my mum. She cleans offices at night, too. I help out.’

‘I’m not saying it’ll be easy. I’m saying you deserve the chance to choose. Let them say no. Don’t say no to yourself first.’

And we did it half in secret.

After class, I sat in his classroom and worked on my essay.

The first draft I wrote was a cliché: ‘I like maths, I want to help people.’

He read it and shook his head.

‘Anyone could say that. Where are you?’

So I started over.

I wrote about 4 a.m. and orange vests.

About my dad’s empty shoes by the door.

‘The first draft I wrote was banal.’

About how my mum learned to calculate medication dosages and now collects medical waste.

About how I lied to her face when she asked if I had any friends.

When I finished reading, Mr Anderson was silent for a long time. Then he cleared his throat.

‘Yes. Send this one.’

‘I lied to her face when she asked if I had any friends.’

I told my mum I was applying to ‘some schools on the East Coast,’ but I didn’t say which ones. I couldn’t bear the thought of seeing her joy and then saying, ‘It’s not going to work out.’

The rejection, if it came, would be mine alone.

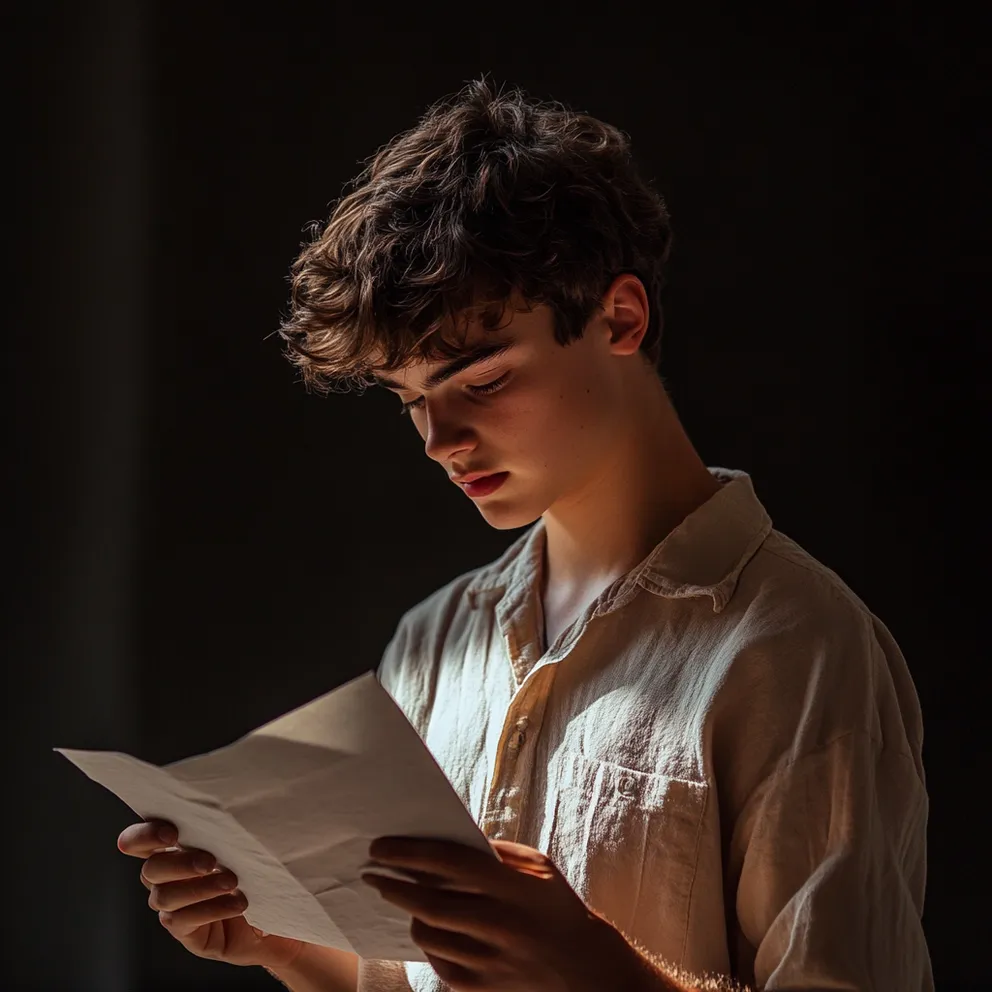

The letter arrived on Tuesday.

I was half asleep, eating velvet.

The phone vibrated.

The letter arrived on Tuesday.

Admission decision. My hands were shaking when I opened it.